Publisher: Desert Dog Books

Published Date: April 6, 2019

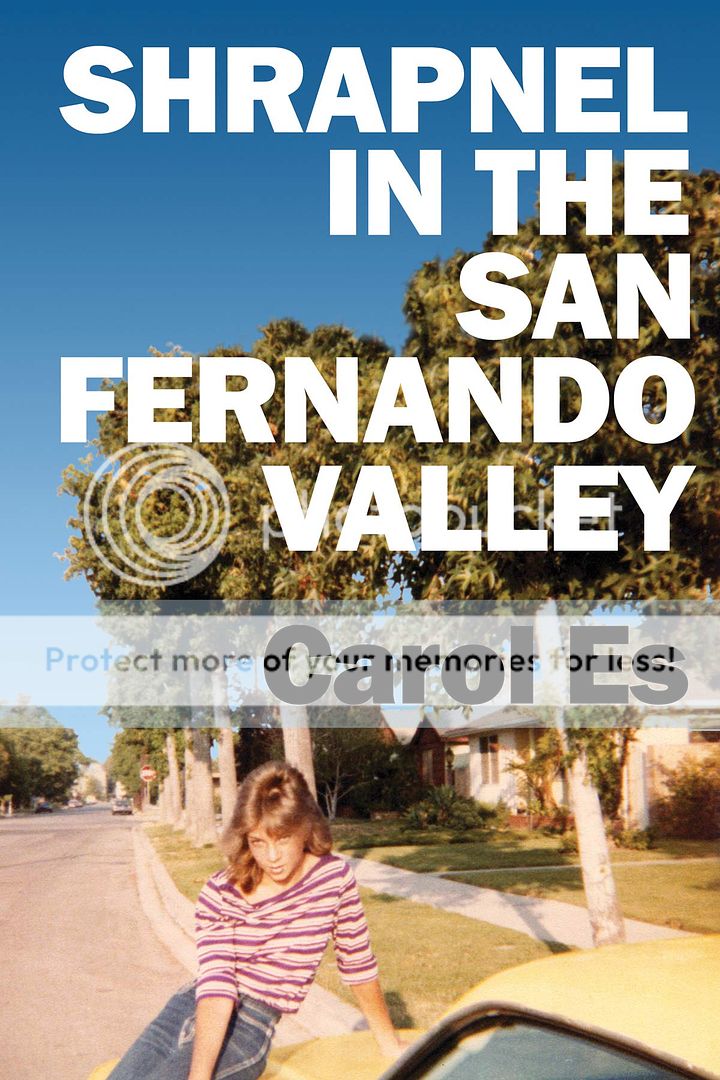

Shrapnel in the San Fernando Valley is a guided tour through a Tilt-A-Whirl life that takes so many turns that you may find yourself looking up from the pages and wondering how the hell one person managed to fit them all into 40-odd years. And many of them are odd years indeed. From a rootless, abusive childhood and mental illness through serious and successful careers in music and art, much of which were achieved while being involved in a notoriously destructive mind-control cult. Carol Es presents her story straight up. No padding, no parachute, no dancing around the hard stuff. Through the darkness, she somehow finds a glimmer of light by looking the big bad wolf straight in the eye, and it is liberating. When you dare to deal with truth, you are free. Free to find the humor that is just underneath everything and the joy that comes with taking the bumpy ride.

Illustrated with original sketches throughout, Shrapnel in the San Fernando Valley is not just another survivor's tale, it's a creative ride where raw and intimate revelations are laid bare. As an artist and a woman finding self-worth, it's a truly courageous, relatable story that will keep you engaged to the end.

Excerpt

1. Chewing on Bullets

The year I turned forty, I got a birthday card from my parents. On the inside my mom wrote, “This is going to be your year!” She couldn’t have known a cold blast of death and sh*t storms were headed straight for us, or how I’d become an abominable wreck and make my way back to the shackles of the R.J. Reynolds’s killing campaign, a.k.a. smoking. I hadn’t smoked a cigarette in over ten years. It felt longer, but who’s counting? I was!

A few years before I reached for the smokes again, I’d been estranged from my older brother, Mike. My life was more or less calm. I’d been fed up with his soapbox lectures about how I’d be going to Hell for being a Jew unless I recognized who my savior was. At this particular moment, we were stuck at a hospice facility in Las Vegas with our dying father. My only savior was a pack of Camels, because Mike and I were fighting about every aspect of our dad’s care.

Three weeks we stayed there. My dad hung on while Mike nearly drove me into a nut house. Two weeks into our stay, I frayed. I took off in my car one afternoon, screeching down Las Vegas Boulevard in rush-hour traffic like a lunatic jonesing for a special kind of crack.

The combination of losing my dad while being trapped in a room with my feral family members pushed me to a breaking point. Only my brother could drive me into levels of such nicotine rage. All those years of breathing clean and clear were for nada. Wasted and meaningless.

I turned my steering wheel to the right, pulling three lanes over from the left, and into the lot of a 7-Eleven. I parked and sat there for a moment to make certain I knew what I was doing. I didn’t.

Mike, who’d been ringing the crap out of my cell phone, was about to get an earful of angry little sister. He wanted to know where the hell I’d run off to.

“Fu** this sh*t!” I exploded through giant tears. “I am so ready to go back to L.A. Though my windows were closed, I’d managed to frighten a lady just outside my car. I watched her quickly skedaddle into the store.

Mike had experienced my outbursts before, but this one seemed to come from the underworld, blasting up out of the ground, like somebody stepped on an IED or something—the blast taking place in my Honda CRV.

I’d been holding it together and keeping my cool, but now I was certifiably losing my mind. He was the older one, yet for most of our lives I’d been the responsible one. Not that it could’ve, or would’ve, ever mattered. He was the goda*ned Golden Boy. My mother always kissed his sh*ts before they went bye-bye.

Several blocks away from the 7-Eleven stood Alliance Hospice Care, where we’d both been staying with my dad while he lay dying. Once the doctors gave Dad seventy-two hours to live, Mike went completely into denial. To him, the place was the Play-doh Murder factory. His plan was to nurse Dad back to health by shoveling gobs of tapioca pudding down his throat.

“Eat, Dad, eat. We gotta get you out of this prison!”

But the place wasn’t bad. It was bright and clean with a big tropical fish tank in the lobby where you could stare at the fish and think about death. The patients’ rooms circled around a pretty courtyard with nice-ish patio furniture, though some of the upholstery was ripped and faded, beaten by the Vegas sun. The staff, too, were super friendly and qualified. All of this was paid for by Medicare, by the way. No way could you find anything like it in Los Angeles.

He had a private room, palatial and homey. As if we were staying in a little cottage in a Thomas Kinkade painting. There were two extra beds, sort of: a daybed too short for Mike’s boney six-foot frame, and a trundle bed underneath. I slept in the trundle bed like a sweater in a drawer, but I spent most of my time in a chair next to Dad’s bed, working on a hand-sewn doll of myself (or a version of me anyway)—an autobiographical character I often use in my paintings and drawings, a thing I call Moppet. She’s a straggly little ragdoll. She looks disheveled and as if she’s about ready to collapse like a push puppet. Moppet usually wears a simple dress, something I’d never do. The dress has a kind of clown collar. “She” is genderless and shaped like a gingerbread cookie with rounded arms and legs, an oval-shaped head and eyes with pupils nearly filled black, like those sad, velvet puppy-dog paintings. She neither smiles nor frowns; her mouth, a straight black line, a lot like me: indifferent. Also like me, she is an awkward child. I suppose she represents my vulnerabilities, my fragility, and what I think of myself, which isn’t much. In fact, she used to wear a dunce cap, but after ten years of therapy it’s been removed.

About the Author

Los Angeles writer, musician, and self-taught artist Carol Es writes for the Huffington Post, Whitehot Magazine, and Coagula Art Journal. She’s been published with Bottle of Smoke Press, Islands Fold, Chance Press, and her Artist’s books are featured in the Getty Research Library, Brooklyn Museum, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts. She is a two-time recipient of the Durfee Foundation’s ARC Grant, a Pollock-Krasner Fellow, and won the Wynn Newhouse Award in 2015.

Los Angeles writer, musician, and self-taught artist Carol Es writes for the Huffington Post, Whitehot Magazine, and Coagula Art Journal. She’s been published with Bottle of Smoke Press, Islands Fold, Chance Press, and her Artist’s books are featured in the Getty Research Library, Brooklyn Museum, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts. She is a two-time recipient of the Durfee Foundation’s ARC Grant, a Pollock-Krasner Fellow, and won the Wynn Newhouse Award in 2015.

Awarded grants in writing from the National Arts and Disability Center, Asylum Arts in Brooklyn, NY, Carol won the Bruce Geller Memorial Award WORD Grant for 2019.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

1 Comments

thanks for hosting

ReplyDelete